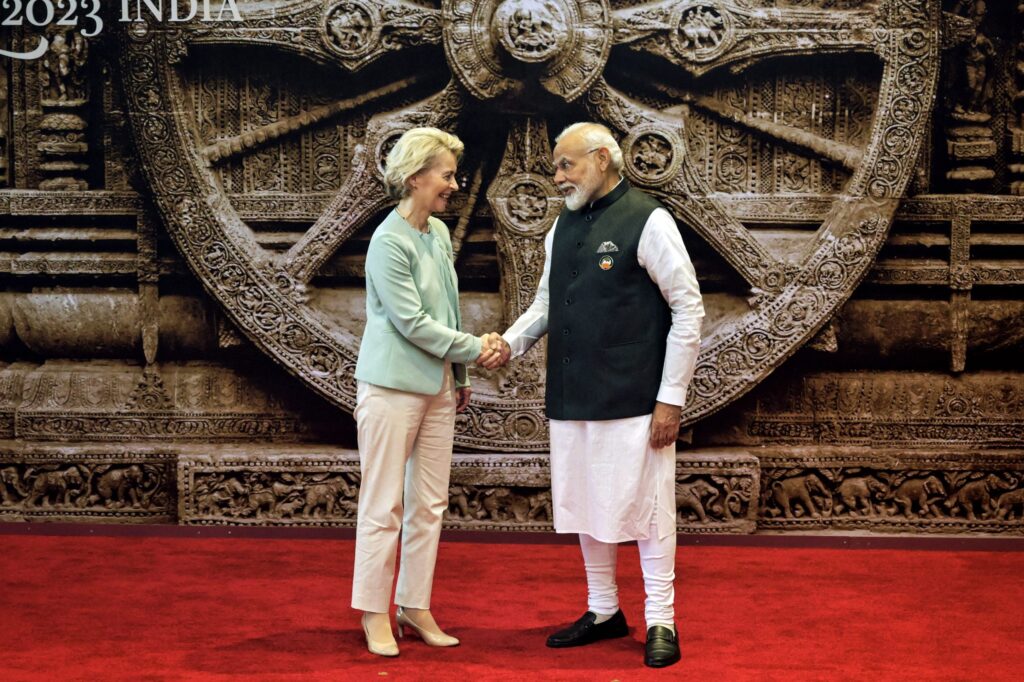

With Narendra Modi on his way to a third consecutive term as Prime Minister of India and the European Parliament reshuffling after the June elections, 2024 appears to be a year to recalibrate EU-India relations.

The European Union and India marked 60 years of bilateral relations in 2022. Although the partnership is gaining momentum under Modi’s leadership, the EU-India dynamic is yet to reach its full potential. potential.

So far, the rapprochement has focused mainly on concluding a free trade agreement (AGLE), but both sides continue to feel pressure from security challenges, prompting the EU to consider expanding relations with India in the context of strategic partnerships

Although there have been conferences since June 2022, a potential deal is on hold as both sides focus on their elections. But that hasn’t stopped commercial advances. Last year, the EU overtook the United States and became India’s largest business partner, A clear indication of an opportunity for deeper strategic exploration.

This is one of the main reasons why experts from the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) argue There is a need to restart relations, with the countries’ respective elections providing a perfect opportunity to re-engage.

A report from the Jacques Delors Institute arguments the same. According to experts at the Paris-based think tank, the decade ahead offers a unique opportunity for the EU and India to deepen their partnership.

China, a shared concern

The EU and India are both navigating choppy waters in their respective relations with China, but they also share common ground for concern.

Geopolitical Monitor Experts describe India-China ties are unique in nature. While Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping may have demonstrated political fabrication, they both lead countries with more than a billion people, which pits them against geopolitical competitors and gives them the ability to influence world affairs, for better or for worse.

There is also strong competition in the economic field. India’s $3.5 trillion economy is still small compared to China’s nearly $18 trillion economy, but analysts predict New Delhi could overtake Beijing as a global growth engine by 2028.

China’s “miracle” phase of expansion is no longer that, and Modi (along with Western governments) have noticed, encouraging Modi to woo companies to diversify supply chains outside of China.

India’s stock market is booming, foreign investment is coming in large amounts, and more governments are interested in reporting business deals.

While Europeans often walk on thin ice with China – as highlighted by the recent visit of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz – they want to make the Asian country play by their rules when it comes to fair trade.

In this sense, the EU and India can further explore ways and join forces, while considering how to address the deepening of Beijing-Moscow ties, which are not favored by either parts.

No “chopped” foreign policy

Unlike previous elections, foreign policy is part of India’s campaign rhetoric. 19% of 35,000 respondents participating in a poll by the India Today group released earlier this year credited Modi for increasing the country’s global stature as their second best achievement.

While analysts say the country has never been tentative about its foreign policy, the past 10 years under Modi’s leadership have marked a visible shift in style or rhetoric rather than substance.

Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, the foreign minister of India, is the person responsible for expressing New Delhi’s recent assertiveness on the world stage. “He doesn’t say a word,” said Vinay Sahasrabuddhe, national executive member of Bharatiya Janata, told Reuters in a interview.

A report from Brussels-based think tank Egmont underlines The expected continuity of the foreign and security policy asserted in New Delhi, the election result not being a surprise.

Experts say there is room in these areas for both sides to foster a true partnership. For the EU, it is a geopolitical imperative to strengthen relations with India and play a stronger defense and security role, particularly through Russia’s war in Ukraine.

(By Xhoi Zajmi Edited by Brian Maguire | Euractiv’s Advocacy Lab)